The ozone layer recovery is one of the few environmental stories that’s actually moving in the right direction. The gigantic ozone hole above Antarctica — once a symbol of global ecological crisis — is now shrinking, and scientists expect the layer to return to roughly pre-1980 levels over most of the world around 2040, and later in the polar regions.

This isn’t just a scientific detail. The ozone layer is Earth’s natural sunscreen. When it thins, more harmful UV radiation reaches the surface, increasing skin cancer, cataracts, crop damage and stress on marine ecosystems. The fact that it’s recovering tells a bigger story: we caused the damage, we identified the problem, and with coordinated global action, we started to undo it.

What’s Happening Now: The Ozone Hole in 2025

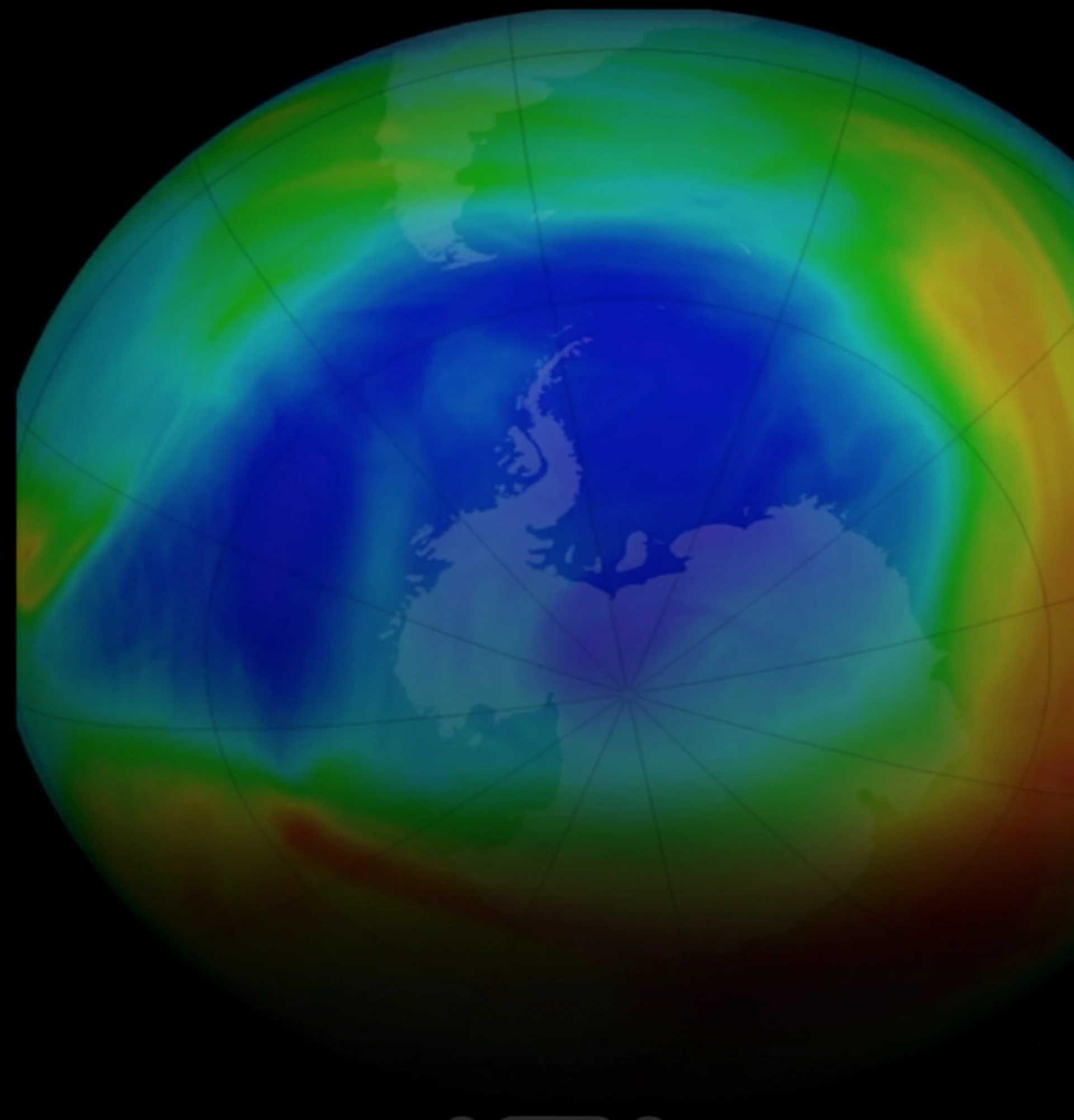

Recent data from NASA, NOAA and European monitoring programs show a clear long-term recovery trend. The 2025 Antarctic ozone hole was ranked among the smallest since the early 1990s, and it closed earlier in the season than in many previous years.

Key points from current observations:

- The Antarctic ozone hole still forms every Southern Hemisphere spring, but:

- It’s forming later and closing earlier.

- Peak size is generally smaller than in the 1990s and 2000s.

- On average from September to mid-October 2025, the hole was about twice the size of the continental U.S., but still smaller than in many earlier years.

- Scientific assessments from WMO and UNEP project:

- Global ozone back to 1980 levels around 2040.

- Arctic recovery around the mid-2030s.

- Antarctic recovery closer to the 2060s.

In short: the hole is still there, but it’s behaving exactly as models predicted after we phased out ozone-depleting chemicals.

How It Started: From Everyday Sprays to a Planet-Scale Hole

The ozone crisis didn’t start in a lab — it started in homes, factories, fridges and hair salons.

1. The Rise of CFCs

From the mid-20th century, industries used chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and related substances in:

- Aerosol sprays (deodorants, hairspray, cleaning products)

- Refrigerators and air conditioners

- Foam production and industrial solvents

These chemicals were considered “safe” at ground level: non-flammable, non-toxic, very convenient. The problem appeared much higher up.

2. The Science Warning

In 1974, chemists Mario Molina and F. Sherwood Rowland warned that CFCs released at the surface could slowly drift into the stratosphere, where intense UV light breaks them apart, releasing chlorine atoms that destroy ozone molecules. Their work predicted that continued use of CFCs would thin the ozone layer over time.

For years, this was mainly a theoretical risk. Then came the proof.

3. The Discovery of the Ozone Hole

In 1985, British Antarctic Survey scientists Joe Farman, Brian Gardiner and Jon Shanklin published data showing an enormous seasonal drop in ozone over Antarctica — a “hole” in the ozone layer.

Some key facts:

- The hole was larger than the Antarctic continent.

- Ozone levels over Antarctica had fallen by more than 50% in spring at certain altitudes.

- The main culprits were human-made compounds: CFCs and related halogenated gases, releasing chlorine and bromine that destroy ozone.

This discovery shocked policymakers. The models hadn’t predicted such a dramatic, localized collapse. It became a global alarm bell.

4. The Montreal Protocol: The Turning Point

In response, governments negotiated the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer, signed in 1987 and in force from 1989.

What the treaty did:

- Gradually phased out production and consumption of key ozone-depleting substances (ODS), especially CFCs.

- Added amendments over time (London, Copenhagen, Kigali, etc.) to accelerate phase-outs and include new chemicals like HCFCs and HFCs.

- Achieved a 98% reduction in controlled ODS compared to 1990 levels.

Without the Montreal Protocol, UNEP estimates that ozone depletion by 2050 would have been 10 times worse, causing millions of extra skin cancer cases every year.

Impact, Context, Pros & Cons of the Recovery

The Upside: What Recovery Brings

Health & Life:

- Fewer cases of skin cancer and cataracts over the coming decades.

- Less UV damage to immune systems and to sensitive populations.

Nature & Food:

- Less UV-B stress on crops and forests, supporting global food security.

- Better conditions for phytoplankton, the base of the ocean food chain and a key carbon sink.

Climate Co-Benefits:

- Many ODS are also powerful greenhouse gases.

- Phasing them out has already avoided the equivalent of hundreds of gigatons of CO₂ and may have prevented up to 0.5°C of additional warming by 2100.

The Complications: It’s Not a Straight Line

1. Slow and Uneven Recovery

Recovery is not instant. CFCs are long-lived; they can stay in the atmosphere for decades. That’s why full recovery over Antarctica is not expected until around 2060–2066, even though we essentially stopped producing the worst substances years ago.

2. Natural & Human Disturbances

Events like volcanic eruptions, wildfires or unusual stratospheric circulation can temporarily worsen the ozone hole in certain years, even with ODS declining. The 2022 Hunga Tonga eruption, for example, may have influenced the behavior of recent ozone holes.

3. New Threats

Scientists are now warning about emerging potential impacts from things like:

- The fast-growing space-launch industry, which can inject emissions into the upper atmosphere.

- Illegal or unregulated production of banned chemicals in some regions.

So while the trend is positive, it’s not a “set it and forget it” situation.

Our Take: Why This Ozone Story Really Matters

The ozone layer recovery is more than a scientific success; it’s a template for how the world can deal with massive, shared problems.

1. Proof That Global Treaties Can Work

At a time when climate discussions often feel stuck, the Montreal Protocol is a real-world example that:

- Science can identify a threat.

- Governments can negotiate binding, global rules.

- Industries can adapt and innovate when regulations force them to.

It’s one of the most successful environmental treaties ever signed — and nearly every country on Earth is part of it.

2. A Warning About Delay

It also shows how slow recovery is, even when we do the right thing. We acted in the 1980s, and we’re still waiting until mid-century for a full return to normal levels. If we wait too long on other issues, especially climate change, recovery timelines may stretch far beyond human lifetimes.

3. A Blueprint for Climate Policy

If policymakers are serious, they can lift several lessons from the ozone story:

- Phase-outs work better than vague voluntary pledges.

- Clear deadlines force innovation (new refrigerants, new tech).

- Rich countries helping poorer ones transition speeds up progress.

Our prediction: you’ll see the “Montreal Protocol model” mentioned more and more in discussions about methane, nitrous oxide and other climate-forcing gases.

Final Thought

The ozone layer story started with everyday products and invisible gases, turned into a planetary crisis, and is now becoming one of humanity’s rare environmental comebacks. It proves that global systems can be pushed to the brink — but also pulled back, if we move early, together, and with real enforcement.

If the world treats climate change with the same seriousness it gave the ozone hole, the next few decades don’t just have to be about damage control. They could be about recovery.

Stay Ahead

“For more updates, insights, and breakdowns on everything happening in environmental science and global climate policy, keep following TopicTric — we cover every major shift the moment it happens so you never fall behind.”